There is an old joke about

accountants and CFOs:

A company’s chief executive

needs to hire a new CFO. He has the field narrowed down to two candidates and

he decides to call them in separately for one last interview. The interview

will consist of only one question.

The CEO calls in the first

candidate and asks, “How much is 2+2.”

The first CFO candidate

answers, “Four.”

The CEO thanks him and lets

him know that he will be in touch.

The second candidate is then

ushered in for his interview and the CEO asks him the same question, “How much

is 2+2.”

The second CFO candidate gets

up out of his chair, closes the door to the office, looks at the CEO and says

in a hushed tone, “How much do you want it to be?”

I tell this story only as a

way to emphasize that companies often have a wide degree of latitude when it

comes to reporting earnings. What’s more, that latitude generally grows during

a bubble.

For example, back in the late

1990s, the technology companies found a way to completely change the way that they

paid their employees and expensed their research and development costs.

Technology companies, up

until that time, had always expensed their R&D upfront, as it occurred.

This was a very conservative stance.

As the bubble in technology

shares grew, things began to change. In order for companies like Cisco and

Microsoft to be able to retain their employees, they had to start to pay them

more in the form of stock options because everyone knew, at that time, that

technology shares only went up.

The only problem with this

was that GAAP accounting did not require companies during this period to

expense the value of the options granted and run that expense through the

income statement. The quality of technology company earnings was, therefore,

starting to collapse.

The trend got even more

egregious as the most talented coders and developers would walk out the door

one day with their best ideas, form a company and turn around and auction it

off to their former employer or one of its competitors for billions of dollars.

R&D, which at one time had been expensed upfront, was now outsourced at no

cost to the company, at least with regard to its income statement. Cisco was

issuing so many options to employees and new shares to start-up companies

without products or revenues in the form of takeovers that CSCO was soon

issuing $25 billion per year in equity securities that would never be expensed.

It was a debacle, and

shareholders never cared about the horrific quality of the reported earnings as

long as the shares were going up. For anyone that cared to look, however, it

was very clear that the economics of the businesses did not justify the share

prices.

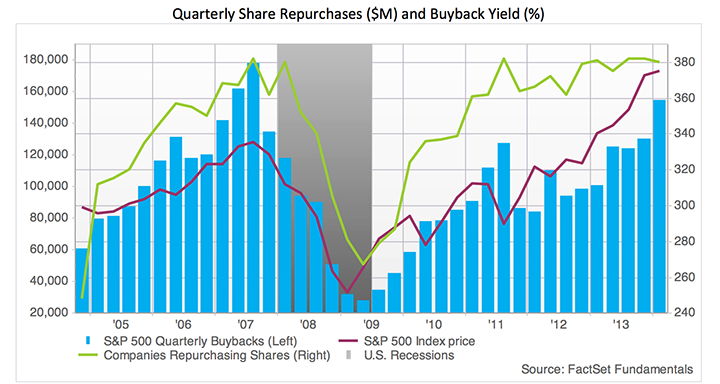

There is a similar

deterioration in the quality of corporate earnings today only it is far more

widespread than what we saw during the technology bubble of the late 1990s.

Today, the item that is now

significantly starting to crush the quality of corporate earnings is the

enormous move to buy back company shares.

The intellectual problem that

I have with current accounting standards is that buying back stock is thought

of entirely differently than is any other corporate expenditure item.

If Caterpillar spends

$100,000 to build a hydraulic excavator and sells it for $150,000, all is well

and the resultant income and expenses are run through the income statement and

investors can track management’s ability to operate the business.

The same thing is true if

they spend $100,000 to build the excavator and sell it for only $90,000.

Investors can see the resulting loss in the income statement and judge

management accordingly.

None of this is true

regarding share buybacks, and this is no small matter. Share buybacks are the

new business of America. I have argued before that this tells us much about

management’s views of their ability to profitably deploy capital in their main

business in the future. They are not positive.

It is, however, boosting

earnings per share meaningfully today as companies can borrow at next to no

cost, thanks to the Fed’s massive intervention in the securities markets, and

buy back shares, thereby reducing the denominator in the earnings per share

calculation.

For those of us that believe

that share prices, broadly speaking, are near the apex of an incredible bubble,

then all of this buying back of company shares represents an incredible waste

of capital, though none of it will ever be expensed according to GAAP standards.

It does, however, give the appearance of boosting earnings per share today,

which is all that seems to matter to investors.

Yesterday, Caterpillar Inc.

reported earnings that appeared to be great. The earnings report was seen as so

good that CAT shares were up more than $4 and the report was seen as a key

reason for the more than 200 point jump in the Dow.

Let’s take a look at these

stellar earnings.

Revenue from machinery sales

was up just 0.6% Y/Y.

Operating profits were

actually down $9 million Y/Y.

Earnings per fully diluted

shares outstanding did manage to jump to $1.63 from $1.45 in the year earlier,

however.

This prompted noted CNBC

commentator Jim Cramer to exclaim, “If

Caterpillar can do this kind of number when things are bad, what number can it

print when things are good?"

So, how did CAT boost EPS with such

poor top and operating line performance?

The answer, of course, was to stop

investing in the business, borrow lots of money and buy back shares.

Capital spending is down $800 million

YTD vs. last year. Despite borrowing an additional $1.4 billion YTD, interest

expense was actually slightly lower in the quarter and the company has bought

back a whopping $4.2 billion in stock so far this year, taking the diluted

share count down nearly 30 million shares.

As a point of reference, share buybacks

this year are running at 178% of capital expenditures compared to just 63% last

year. No one believes that we shouldn’t expense capex over time, so why

shouldn’t we run gains or losses on share buybacks through the income statement

so that investors can get a better sense of management’s ability to deploy

capital? After all, we are no longer talking about paltry sums here and we need

to account for this activity in a better way.

Now, let’s get back to Jim Cramer. He

wants to believe that CAT’s earnings numbers will be spectacular when things

improve in the economy.

Given the fact that the savings and

investment rate in the U.S. has crashed due to the Fed’s policy of artificially

driving interest rates towards zero, just how does Mr. Cramer expect the

economy to improve?

Companies are clearly saying that they

can no longer earn a return on the capital deployed in running their

businesses, so they are clearly deciding to give up and they are returning the

capital to shareholders. Corporate America doesn’t believe that things will

improve in the economy, not enough to justify increased investment at the

expense of reducing share buybacks anyway.

Is it a good idea for companies to

return capital through share buybacks?

That, of course depends on whether the

shares are cheap or expensive. Sadly, as John Hussman reminds us with the

following graph, companies are generally extremely poor market timers. As for

me, I am taking 50 cents out of a company’s earnings report for every dollar of

stock that they buyback given my view that the market is extremely overvalued. If you believe that stocks are cheap, then you should

add a few cents to net income for every dollar of stock they buyback.

Those undertaking the latter action

should give some serious thought to the Mr. Hussman’s graph, however:

Disclaimer: Nothing on this site should

be construed as investment advice. It is all merely the opinion of the author.

No comments:

Post a Comment