The most important

thing is this (oil price collapse) is a massive tax cut for the world. This is

really good stuff for the world.

Larry Fink

CEO Blackrock

December 11, 2014

Lower oil prices are

like a tax cut to the economy, so in terms of macroeconomic impact, it’s a

positive.

Jacob Lew

U.S. Treasury Secretary

December 11, 2014

Despite the impressive

recent gains in natural gas and crude oil production, the U.S. is still a net

importer of energy. As a result, falling energy prices are beneficial for our

economy.

Over the near term,

this will lead to a significant rise in real income growth for households and

should be a strong spur to consumer spending. Since energy expenditures

represent a higher proportion of outlays for lower income households, falling

energy prices disproportionately raise their real incomes. Also, because such

households are more liquidity constrained, with budgets that often bind

paycheck to paycheck, they have a higher tendency to spend any additional real

income.

As a result, much of

the boost to real household income from falling energy prices is likely to be

spent, not saved.

Bill Dudley

President New York Federal Reserve Bank

December 1, 2014

Here we have the head of the world’s largest asset manager,

the CFO of the U.S. government and the globe’s chief money printer and regulator

of the world’s most important banks all telling us that crashing oil prices are

a good thing. Consumption will go up and savings will fall as a result of lower

oil prices and these are, allegedly, good things.

Personally, I have never seen an issue that more starkly

contrasts the Keynesian view of the world, as referenced above, with that of

the Austrians.

Keynesians focus on GDP, aggregate demand and animal spirits.

Austrians focus on savings and capital creation, the entrepreneur’s focus on wealth

creation and the avoidance of the malinvestment that comes from money and

credit creation from thin air.

Keynesians want to boost consumption and penalize savings following

a bust by artificially pushing interest rates lower. Austrians want to point to

rates being too low during the bubble phase as being the cause of the

subsequent crash and economic hangover and they argue that lower rates for

longer will only create bigger problems in the future.

Oil’s collapse gives us a perfect perch from which to

compare these contrasting economic views.

As we saw above, the typical Keynesian view is that the oil

price collapse should increase consumer demand and decrease savings. These are

thought to be good things.

Austrians view the oil price collapse with horror. Savings

(real capital) was wasted on a truly epic scale as malinvestment ran amok

throughout one the world’s biggest and most important industries. This is an

industry that has seen annual upstream capital expenditures increase by about

75% to nearly $700 billion in the past five years. Pretty much all of that

spending appears to have been wasted.

How could this happen?

Keynesians, it seems, don’t really care about the cause of

all of this wasted capital. In the U.S. and Europe the only concern seems to be

with whether or not the oil price collapse will lead to increased consumption

and decreased savings. Both of these effects are cheered on by the Keynesians.

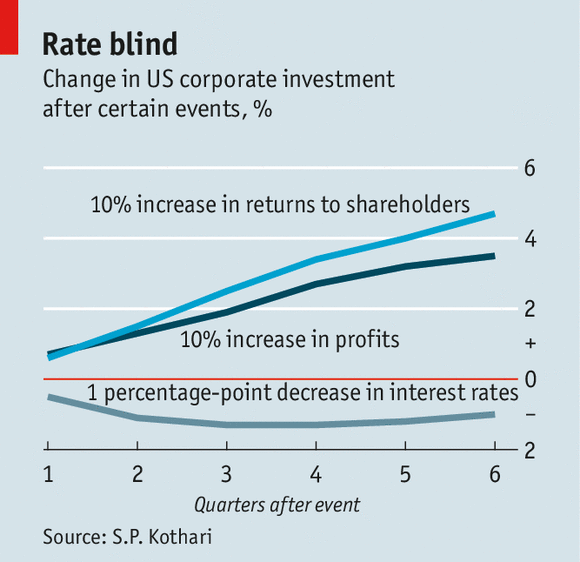

Austrians point to artificially low interest rates as having

impacted the structure of production and consumption. Artificially low rates

appear to have been a prime mover in China’s titanic infrastructure build-out

of the past five years. This created a nearly insatiable demand for energy on

the part of China, the major incremental driver of nearly everything on the

planet for much of the recent past. This demand drove oil prices relentlessly

higher over the past few years.

Alas, the Chinese real estate miracle appears to have

crested and, with real estate prices starting to fall, the infrastructure

build-out has stalled. Energy demand is, therefore, falling relative to

previous expectations.

Oil production, especially in the U.S., boomed with the rise

in capital spending that came from artificially low interest rates and strong, but artificial, oil demand. Despite the overall fall in savings in the U.S. over the

past decade, whatever remained of the pool of savings was made available for

oil production. In fact, oil production in the U.S. is up about 80% from its

low point and the high yield market has come to be dominated by borrowers from

the oil patch.

To the Austrians, looking back at the oil boom, it was lots of money and credit from thin air that drove the malinvestment that is now being revealed. They question whether pushing the savings rate lower from the current miniscule levels, a move that the Keynesians cheer, will allow for adequate capital spending in the future to drive any wealth creation in the U.S. They also worry about why anyone would ever want to create and deploy capital (savings) any longer if it always seems to be wasted. Malinvestment is simply a reduction in the already paltry rate of interest that is currently being paid on savings and it does not bode well for future capital creation or future real GDP growth.

Until recently, everyone thought that increased U.S. oil

production would lead to American energy independence and that this was a good

thing. Now, it seems like the Keynesians are telling us that wasting a few

trillion dollars in the oil patch while blowing up the junk bond market was

also a good thing. Who knew?

I’ll stick with the Austrian line: The crash in oil prices

is exposing malinvestment that was driven by central bank fostered easy money

policies which destroyed wealth, deters future savings and wealth creation and,

as a result, destroys future growth opportunities.

Disclaimer: Nothing on this site should

be construed as investment advice. It is all merely the opinion of the author.